The Moral “Grey Zone” of Nazi Collaboration

Jewish police in the Węgrów Ghetto

WikipediaThere’s a four-letter word that a Jew might use to call another Jew a traitor, in the harshest way possible: kapo.

During the Holocaust, Nazis put a small minority of Jews in charge of carrying out their orders. After the war, some of those Jews were accused of abusing their positions. Holocaust survivors sought vengeance against kapos, and tried them in specially-created Jewish honor courts in Europe and state courts in Israel.

This largely-forgotten history that reveals the complexity of victimhood is fascinating to me as a journalist. It also resonates with our current cultural moment, where moral ambiguity is everywhere: from TV shows like “Squid Games” to acrimonious political debates over racial and social justice. Post-Holocaust discourse sought to establish a clear line between victim and victimizer, right and wrong, good and evil. As I learned more about the kapos, I started to realize that those distinctions can sometimes be arbitrary – particularly when the moral choice isn’t always clear.

As a host of the podcast Adventures in Jewish Studies, I explore the Jewish honor courts and their role in processing the trauma of the Holocaust and reestablishing Jewish communities with historian Laura Jockusch, an associate professor of Holocaust Studies at Brandeis University and co-editor of “Jewish Honor Courts: Revenge, Retribution, and Reconciliation in Europe and Israel After the Holocaust,” and Dan Porat, a professor of history at Hebrew University in Jerusalem and author of “Bitter Reckoning: Israel Tries Holocaust Survivors as Nazi Collaborators.”

Kapos played a role in almost every aspect of Nazi persecution, from the ghetto police and those who drew up lists of fellow Jews for deportation, to kapo doctors and nurses, to those who worked in the gas chambers and crematoria. But kapos were not a distinctly Jewish phenomenon.

“Kapos existed in all of the enslaved nationalities that you find in the concentration camp populations. And of course the idea behind it was to weaken the victims, to make them complicit in the concentration camp system and its oppressive measures,” Jockusch said.

The kapo system allowed fewer SS staff to run the camps. It also helped to spread discord among the prisoners. Some kapos did the bare minimum, but survivors also recount horrific cases of kapos going too far, “because in some sense, they were doing the work for the SS. So we do have a lot of evidence of physical violence and sexual abuse,” Jockush said.

“But there are also many examples of kapos who actually tried to protect the prisoners who were subordinate and tried to organize better conditions for them. So being a kapo doesn’t necessarily mean that you were sadistic and murderous and brutal – that perhaps is the little element of choice there,” she said.

Collaboration didn’t just happen at the individual level. Occupying Nazi forces convened Jewish Councils, or Judenrat, tasked with carrying out Nazi policies within Jewish communities. The Nazis specifically chose influential community leaders, like rabbis and successful businessmen, to ensure that Jews would listen to them.

Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski and other officials pose for a group portrait in the Jewish Council’s headquarters, Lodz Ghetto, January 1941 (US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Judith M. Shaar)

The role of the Jewish Councils has long been a controversial issue, raised again recently with allegations that the hiding place of Anne Frank and her family was betrayed by Arnold van den Bergh, a prominent Jewish businessman and a member of the Jewish Council of the Netherlands.

Even the term “collaboration” is problematic, Jockusch says, because “that implies a certain equality in the partners that collaborate,” raising the question of whether “it actually is legitimate to use the word in the Jewish context because of the total inequality of power and the singling out of Jews for collective mass murder, no matter how they behaved.”

Still, after the war, many survivors did blame the Jewish Councils for selling out their communities. In her book “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil,” journalist Hannah Arendt made the inflammatory assertion that the Jews participated in their own destruction through the Judenrat’s collaboration with the Third Reich.

After the war, Jews reckoned with feelings of anger, powerlessness, and survivor’s guilt. It was easy to blame the Jewish Councils, the Jewish police, and the kapos. But doing so, Jockusch says, “blows out of proportion the power relationship that these functionaries actually had within the system of oppression, and that they were victims themselves.”

In the immediate aftermath of the war, though, there was a desire for revenge. There were many accounts of survivors attacking former block leaders or other functionaries, or former members of the Councils. These attacks took place in Israel as well, on the street, at the beach, in coffee shops, and at weddings and bar mitzvahs.

A Holocaust-era ‘Kapo’ leader armband, worn by a Jewish inmate tasked with administrative functions. (Public domain)

“The whole Israeli public felt that these people were the ones who basically brought about this catastrophe or basically enabled the Germans to take the Jews, in the terms of the time, as sheep to the slaughter,” Porat said. “How was it that the Jews didn’t resist? They didn’t resist, the argument went at the time, because the leadership of the Jewish community betrayed the nation.”

Such cases of extrajudicial violence were not limited to Israel and Europe. In 1950, a Holocaust survivor in New York, Benjamin Krieger, spotted a man who he believed had beaten him and killed his brother at the Mühldorf concentration camp in Germany in 1944. A mob chased the man, and the story made it into the major papers. The American Jewish Congress stepped in and set up a tribunal to try the case, in order to avert a public relations disaster.

“This is a time when Congress is debating whether to allow for more people from the DP camps to come to the United States, and having this case in the major newspapers in the United States depicting Jews as murdering one another in the camps will not give a good impression and it will not allow to increase the number of Jews coming from the DP camps,” Porat said.

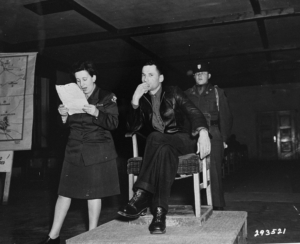

Willi Zwiener, a kapo who turned against his fellow defendants, testifies through an interpreter at the trial of former camp personnel and prisoners from Dora-Mittelbau. To his left the interpreter, Nelly Singer, reads Zwiener’s written statement, while behind him stands his guard, Pfc. Ernest Westerrode. (US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park)

Cases of vigilante justice concerned Jewish leaders across Europe as well, who set up honor courts to try accused Nazi collaborators. There is a long history of rabbinic courts as well as secular courts that arbitrated conflicts between Jews. After the Holocaust, many Jews in Europe didn’t trust state courts to handle what was essentially seen as an internal Jewish issue. “There was a strong sense that it’s an inner Jewish matter that needs to be handled within the Jewish community,” Jockusch said.

So-called “honor courts” were established across Europe to handle cases of Jewish collaboration. “The honor court sentences often involve a moral rebuke that the verdict of a court case would be publicized within the community,” Jockusch said. “And there was this sense of ‘cleansing’ one’s own ranks from those who had acted against the Jews and who should not be earning membership in the Jewish community after the war.”

In Israel, some Holocaust survivors wanted to leave the past behind. Others thought that the new state of Israel needed to be cleansed of traitors. Survivors filed complaints with the police, but there was no legal framework for prosecuting the cases. In 1950, Israel passed the “Nazis and Nazi Collaborators (Punishment) Law.”

The law criminalized crimes against humanity, war crimes, and “crimes against the Jewish people.” The law was unusual. It was retroactive, applied to crimes committed outside the country, and required little evidence. The most serious charges mandated a death sentence.

Jewish prisoners in Plaszow at forced labor. The man at right is a Kapo. (US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Leopold Page Photographic Collection)

In the early 1950s, there were around 350 investigations in Israel of alleged collaborators. About 40 of those eventually went to trial. And of those, about two-thirds were convicted. The law was also used to try Adolf Eichmann in 1961 and John Demjanjuk, known as “Ivan the Terrible,” in 1987. But it was mainly used to go after kapos.

In 1952, a former kapo, Yehezkel Jungster, was accused of murdering other Jews. Those charges were dropped because there were no eyewitnesses or direct evidence to the murders. But there were witnesses who recounted how he beat and tortured Jews. Jungster was found guilty of crimes against humanity, which at the time mandated the death penalty. The judges sentenced him to death, but also expressed discomfort with the extreme punishment. Israel’s Supreme Court overturned his sentence, and sent him to two years in prison instead. His health quickly deteriorated, and after a few months he was released and then died.

“And with that,” Porat said, “the prosecution understands that it was wrong to see these Jews as equal to the Nazis.”

Further trials continued to draw the distinction between the former kapos and the Nazis who oversaw them. Many of the kapos argued that they used their positions to help camp inmates.

Rudolf Kasztner negotiated with Adolf Eichmann in the hope of saving hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews. He was tried for collaboration in Israel and later murdered by a far-right group. (Wikimedia Commons)

The kapo trials could be compared to the reconciliation courts created in the 1990s in South Africa after apartheid, and in Rwanda after the genocide. They were meant to heal communal wounds and rebuild trust. Unlike a traditional court, the Jewish honor courts required both accuser and accused to present witnesses and provide oral testimony.

“And so it was really more about working through the past as a community and establishing truth than about the law,” Jockusch said.

As time went on, the view of kapos changed. There was a sense that they too were victims, forced to survive in an inhumane environment. The Italian-born Holocaust survivor Primo Levi wrote an influential essay in the 1980s called “The Grey Zone.” He argues that the reality of life in the camps couldn’t be reduced to binary divisions of good versus bad, us versus them, victim versus persecutor. That said, he stressed, he was not trying to erase the distinction between the two. He wrote, “to confuse [the murderers] with their victims is a moral disease or an aesthetic affectation or a sinister sign of complicity; above all, it is a precious service rendered (intentionally or not) to the negators of truth.” Levi’s “grey zone” was a way of acknowledging the kapos’ victimhood as well as their guilt.

“The kapos who stood trial in Israel, at least most of them, were in that gray zone. They were victims, undoubtedly they were victims, but they also acted in questionable ways when they beat people, when they took their food, when they harassed and did other horrific things,” Porat said.

Jewish police detain a former Kapo who was recognized in the street at the Zeilsheim displaced persons’ camp in Germany. (US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Alice Lev)

The story of the kapo trials complicates the victim/perpetrator binary. To accept that there is a “grey zone” changes how we see victims.

“Primo Levi says, look, we cannot judge these people in the gray zone, but we must morally discuss these cases and deliberate them without coming to a conclusion, because we, as people who did not live through the Holocaust, did not experience it, cannot judge them,” Porat said.

“It’s very easy to sit here today in the 21st century and say ‘I would have acted in this way or that way.’ I think if we learn these cases, we understand that it’s much more complex.”

The Adventures in Jewish Studies podcast was created to fulfill the Association for Jewish Studies’ mission of fostering greater understanding of Jewish Studies scholarship among the wider public. Podcast episodes are designed to take listeners on exciting journeys while exploring a wide range of topics, from the contemporary to the ancient, in ways that are informative, engaging, and fun. Each episode features the voices of AJS members as they share their expertise and research with listeners. Find out more here.