Nathan Salsburg: On Psalms

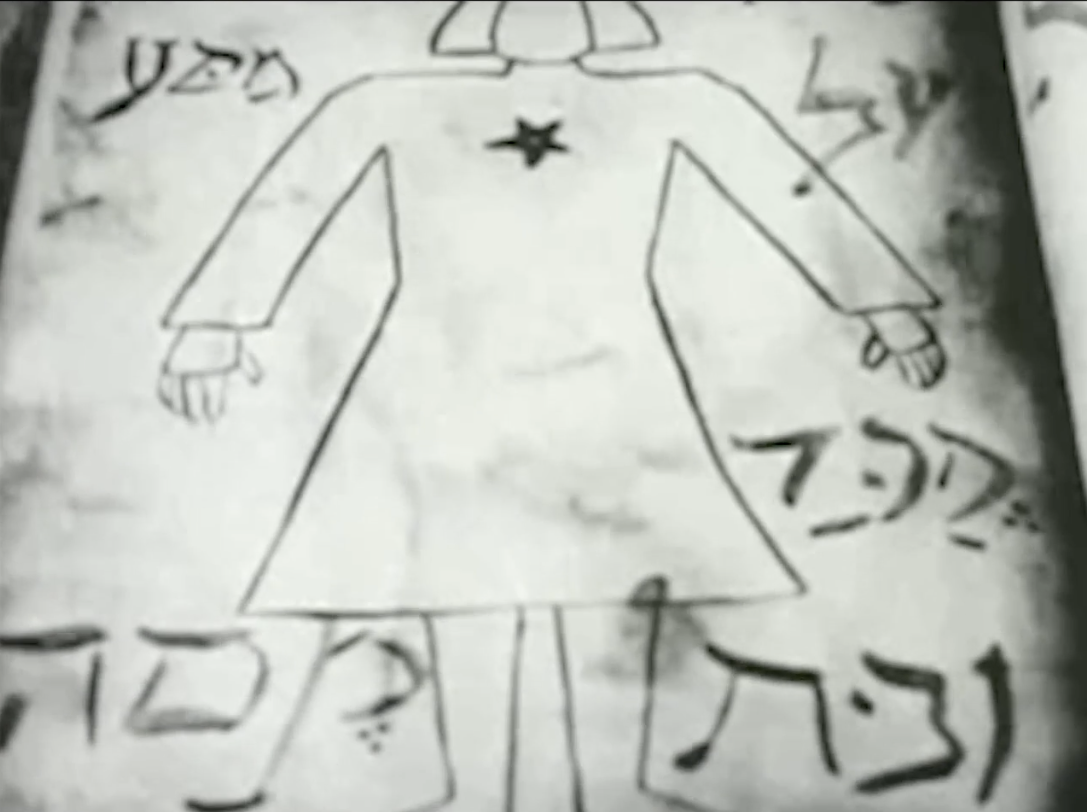

My name is Nathan Salsburg. I’m a guitar player and composer living in Kentucky. In 2016, in a desire for some kind of rigorous and creative Jewish engagement, I began an irregular practice of opening a bilingual Book of Psalms at random, scanning the English (I don’t speak and can only haltingly read Hebrew) of a particular chapter for passages that resonated conceptually and emotionally, as well as scanned rhythmically.

Stirred (and/or challenged) by the words, I worked to thread them into new melodies, with the ultimate intention of making them satisfactorily singable. And in August I released an album called Psalms, consisting of these new arrangements and recorded in their entirety, somehow, over the long course of the interminable year of 2020.

Prior to this, my formative experiences with Jewish music were collective and participatory, at synagogue and summer camp in the ‘80s and early ‘90s, where the acoustic guitar-driven repertoire — combining liturgical Hebrew with contemporary English translations and Israeli folk song — was meant to be sung with maximum physical investment (jumping, shouting, dancing, swaying) for maximum emotional return, which it absolutely delivered. Its earnestness was its cardinal virtue, as it provided an experience of catharsis similarly guileless and really quite liberating for the young Upper Southern/Midwestern Jew I was. It was not, however, music that I could carry into adulthood. I became too old for summer camp; I stopped attending synagogue with any regularity; I sought more than unadulterated emotionalism. I became drawn, then, to Jewish music in which I was incapable of participating: in time, klezmer and cantorial performances on 78-rpm records; in space, the devotional traditions of Sephardic and Mizrahi communities.

So when I heard Dark’cho, David Asher Brook and Jonathan Harkham’s 2004 album of traditional Chasidic melodies and liturgical pieces, I was smitten by it and brought it in close. It was delicate, intentional music, made by sensibilities I felt in tune with. It was sung quietly and played sparsely on instruments I might have chosen. Its spirit was of private meditation as opposed to collective ecstasy; its sound more of seeking than of finding. It was the stuff of aspiration, and it served as a guide to the practice from which Psalms emerged.

Despite the solitary genesis of the songs on this record, I both couldn’t and wouldn’t have made it alone. The contributors, near and far, came to feel like a kind of creative chavurah—a collaborative fellowship that imbued the songs with a vitality of which a sole agent would be incapable. The piece that reflects this spirit most explicitly turns out to be the one non-psalm on the album, and the only one sung in English. “O You Who Sleep” is a lightly finessed adaptation of Raymond P. Scheindlin’s translation of a Hebrew poem by Judah Halevi: the medieval physician, poet, and thinker whom Gershom Scholem called ”the most Jewish of Jewish philosophers.” It’s the fullest band arrangement, and makes the loudest racket (very relatively speaking), before it transitions into a short, but similarly cooperative, singing of the first two verses from Psalm 96.

“O You Who Sleep,” as I title it—although Halevi began other poems with this phrase—is a call to action:

Childishness* is chaff to be thrown off:

Awake!

An individual is being addressed—though it could; rather, it should be applied to a community, a faith, a species—and urged to break free from the fetters of time, and turn its attention to the eternal.

In the river of those souls

That unto bliss the radiant faces flow.

But in its entreaty to

Greeting you in gray with lessons every dawn

I hear a profound resonance for the current desperate moment: a challenge to liberate ourselves, all of us, from our folly, ignorance, selfishness, moral flabbiness, existential myopia, and embrace—or more so embody—a decisive boldness of thought and action. If we could manage that liberation, we’d manage the liberation of all people, all species, all life on this planet. And thus, as Psalm 96 enjoins:

Sing to the Lord, all the earth

Sing to the Lord, bless Hashem

Proclaim Hashem’s salvation from day to day.

*This I changed from Scheindlin’s “childhood,” which for me lacked the necessary negative connotation.