Breaking the Mold: Kafka’s Unexpected Love for Yiddish Theater

As a curator, I’ve learned that, in the process of organizing an exhibition, there’s always a moment when I discover a particular angle or aspect of the overall subject matter and suddenly want to devote the entire exhibition to that topic alone. In the course of working on the exhibition Franz Kafka, which was curated by a group of scholars for its original presentation at the Bodleian Library in Oxford in the spring of 2024 and which I then adapted for the Morgan Library & Museum, that moment came when I learned about Kafka’s first encounter with the Yiddish theater in the winter of 1911-1912.

Kafka was raised in an assimilated family whose engagement with Judaism was very limited, so much so that the cards sent out by his father Hermann inviting guests to young Kafka’s bar mitzvah read “I cordially invite you to the confirmation of my son Franz, which will take place on June 13, 1896 at 9:30am at the Zigeunersynagoge.” As a young man and well into his twenties, Kafka generally followed his family’s lead. But in 1911, when he was 28 a ragtag Yiddish theater troupe from Lemberg (Lviv, Ukraine) stopped in Prague to give a few performances in a café. Kafka and his best friend Max Brod went to one performance… and then another, and another, and another. For a brief but intense period, Kafka became a devotee of Yiddish theater: he wrote about the performances at great length in his diaries; he developed crushes on the actresses (a postcard he owned depicting one of them, Flora Klug, is in the exhibition); he became friends with the head of the troupe, Jizchak Löwy, and he eventually ended up giving one of his very few public talks on Yiddish, as the introduction to an evening of recitations and songs by Löwy. I was interested in the degree of his commitment – coming from a man who is famous for his inability to commit – and I sought out books to deepen my understanding, including the scholar Evelyn Torton Beck’s Kafka and the Yiddish Theater and theater historian Nahma Sandrow’s Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater).

One of the many discoveries I made in my reading was the fact that the plays that Kafka saw in Prague had been fundamentally shaped by the Yiddish theater scene of New York’s Lower East Side. That world was incredibly dynamic: the types of plays being performed ranged from Yiddish versions of Shakespeare to shund (melodrama) to more realistic works by playwrights like Jacob Gordin. The individuals involved – playwrights, actors – were larger than life, and their audiences were passionately engaged in each new production and appearance by their favorites.

In becoming one of those theatergoers, Kafka was acting in a way that contradicted every instinct he had inherited from his family and his community, instincts that told him to keep his distance from anything too overtly Jewish. And he defended and doubled down on this interest, introducing Löwy to his father and reassuring the audience, before Löwy’s recital, that “once Yiddish has taken hold of you and moved you – and Yiddish is everything, the words, the Chasidic melody, and the essential character of this East European Jewish actor himself – you will have forgotten your former reserve.”

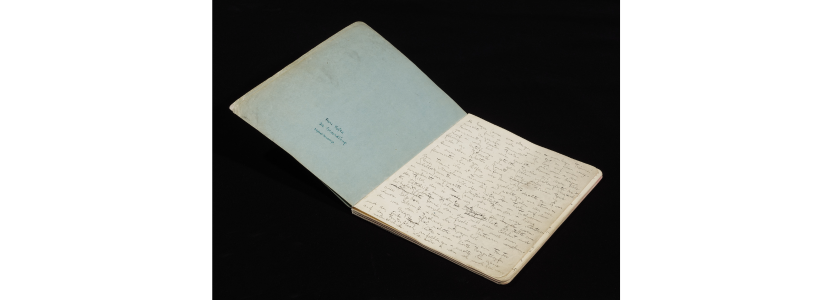

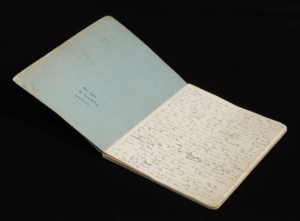

Perhaps most significantly, Kafka’s profound engagement with this world immediately preceded his own literary breakthrough, the writing of the short story The Judgment in a single night in November 1912. After years of false starts and pieces abandoned midway through, this story opened the floodgates for him, creatively. Just a few weeks afterwards, he was writing The Metamorphosis. (The manuscripts of both stories are on view in the exhibition.)

Image Credit: The first page of Franz Kafka’s most famous story Die Verwandlung ( The Metamorphosis ) with its puzzling opening sentence of Gregor Samsa waking up from uneasy dreams and finding himself transformed into an insect. MS. Kafka 18A, fol. 1r © The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

Image Credit: The first page of Franz Kafka’s most famous story Die Verwandlung ( The Metamorphosis ) with its puzzling opening sentence of Gregor Samsa waking up from uneasy dreams and finding himself transformed into an insect. MS. Kafka 18A, fol. 1r © The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

In the end, I knew I couldn’t make the whole exhibition about the influence of the Yiddish theater on Kafka’s life and work, but I was grateful to be able to borrow a Yiddish theater poster from the Thomashefsky Collection at the New York Public Library for the Morgan iteration. It shows the Adlers, Jacob and Sara (parents of Stella Adler), appearing in a 1901 production of Gordin’s play Der vilder Mentsh, which Kafka saw performed in Prague on October 24, 1911. Through this and other curatorial choices, I hope to draw attention to a world that I too fell in love with in the course of working on this project. See the exhibition through April 13 at the Morgan Library & Museum.

A graduate of Columbia University, where she specialized in early modern English literature, Sal Robinson worked in publishing for ten years as an editor for international literature at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and Melville House. She received her MLIS from Long Island University in 2015 and worked as an archivist and cataloger for a number of New York arts and cultural organizations, including PEN America, the American Academy in Rome, the Keith Haring Foundation, and the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation. She started at the Morgan Library & Museum as a cataloger on the Leon Levy project in 2016 and moved into a curatorial role in 2019. In 2021, she was named the inaugural Lucy Ricciardi Assistant Curator in the department of Literary and Historical Manuscripts.

*Image Credit: Franz Kafka, Altstädter Ring, Prague. © Archiv Klaus Wagenbach