Hiding in Plain Sight

Filmmaker Christiane Arbesu’s new film, I am Judit, explores the life of Holocaust survivor Judy Sleed in a captivating portrait of Sleed’s resilience and inflatable joy, despite her harrowing childhood. Watch the film here.

The Hidden Story

For 20 years, Judy Sleed hosted a local talk show telling other people’s stories on a local access television station in East Hampton, New York. But she had never told her own story as a Holocaust survivor. She had never even talked about it with her children.

I met Judy through the executive director of the TV station when I was screening potential subjects for a new show highlighting elders and their contributions and connections to the East End community. What stood out was that despite her devastating childhood and some painful times later in her life, Judy exuded joy. Her laughter during our conversation was intoxicating.

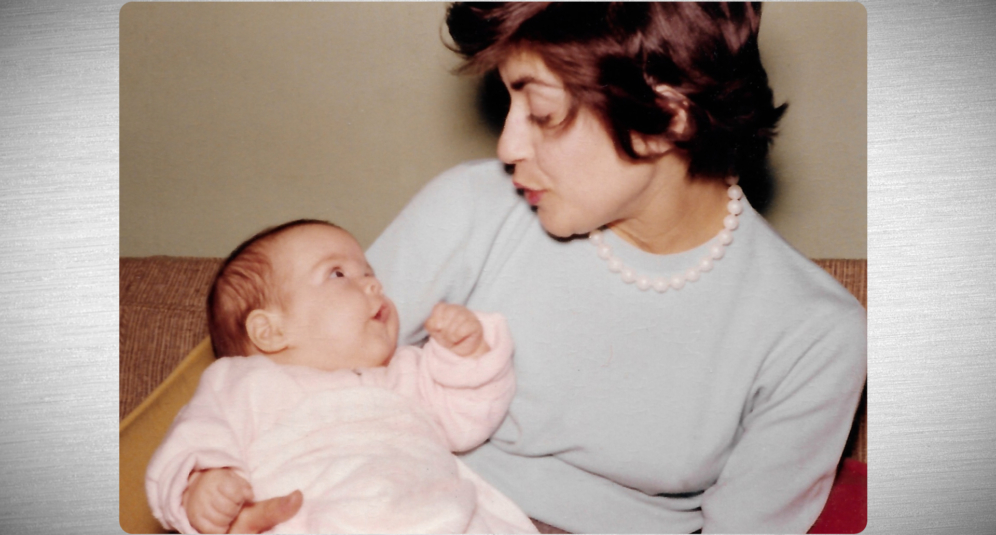

I felt an extra connection to Judy when I found out that she was born in Budapest, Hungary on April 30, 1932, the exact same birthday as my mother. I knew that I had to make a documentary about her. I had to help her finally tell her story.

Judy made it very clear from the very beginning that she didn’t want to focus on her suffering. But she agreed to talk about it because she wanted to make sure that what happened to her would never happen to anyone else. She also realized that she should have told her children about her experiences in the Holocaust but she had wanted to protect them from her pain and suffering as her mother had tried to do with her. Judy said that when she was a child, her mother covered her ears when her parents talked about what was going on in Europe.

Judy’s mother was listening to the radio and heard the order for Jewish women between the ages of 30 and 60 to report to the train station depot in South Budapest Monday morning at 7:00 a.m. She wasn’t going to be late because she was proper and always on time and did what she was told.

Did Judy’s mother know the extent of the brutality? She talks about the night of October 22, 1944, when her mother said goodbye to her and told her that no one will ever love her as much as she does, that she was a good girl and that people will love her. Her father and brother had already been taken away by soldiers abruptly during a family dinner, so she was suddenly all alone at age 12. Judy says she doesn’t know what her mother really knew or why she listened to the authorities and left.

One of my favorite scenes in the film is at Judy’s daughter, Jody’s house, when Judy reads from a play she wrote about her experiences in the Swiss-occupied home for children where she ended up. Judy survived the Holocaust simply by walking out of a building with a massive hole in it. The soldiers had rounded up the children whose parents were gone and placed them in a bombed out building. In a split second, Judy decided to simply walk out of a huge hole in the wall. She decided she had nothing to lose because everyone had been taken away from her. She never looked back and no one tried to stop her. She searched the streets and homes for people she knew and finally found her cousin Eva who placed her into a Swiss-occupied home for children in 1944.

It was in this home where Judy met children varying in ages who were in a similar situation – alone without their family. Judy remembers that she met a little girl named Gabby who was four years old and very well dressed. Judy had dreams of adopting her. The other experience that stands out is when Eva delivered the postcard that Judy’s father wrote to her to let her know that her family was all together and that they were okay. “Only God will help us,” he wrote. She still has the postcard. It was much, much later that Judy learned by chance through a reading group in the Hamptons that the Nazis made the Jews write postcards to their families right before they were all being led to the gas chamber.

The intergenerational trauma is apparent throughout the film. Her daughter and son, Jody and Jeff, felt left out because Judy didn’t share her experiences with them. They knew they weren’t allowed to watch shows about the Holocaust, but they didn’t know why. Jody early on in the film says she tried to adapt. Jeff’s sadness for his mother’s plight is apparent by the way he looks and speaks. He holds back tears as does Jody. As the film unfolds and Judy reads from a play she’s written about her time in a Zionist house, we see her children crying and hugging their mother and understanding her pain.

The film juxtaposes her childhood experiences with her present-day life in an interview style and follows her on her daily activities in the Hamptons. Stock footage and personal photographs and letters saved by Judy’s surviving relatives, take us back in time. Judy shares key memories – the day her father and brother were taken by soldiers from her house while they were having dinner. She remembers her piano teacher who gave her lessons and she talks about making mistakes and her teacher correcting her from the kitchen. Judy still holds on to those good memories of her childhood – the lessons, listening to the radio, dancing with her father.

Soon after the war ended, Eva helped Judy get her papers to go to the United States. Judy had an aunt Rose who left for New York City many years before the war started and that is where Eva sent her to live in 1946 at the age of 14. Judy calls Eva her savior.

I am Judit is a poignant reminder that we must hear these stories to remember the Holocaust. It is not a distant memory; it’s a living history. In an era where some deny the Holocaust happened, Judy’s message echoes loud and clear: forgive, love, and never forget.

Judy’s essence is a living testament to resilience—a blinding light of strength that emanates from her heart of gold. In her presence, a simple smile or hug becomes a powerful encouragement not only for me, but for anyone fortunate enough to share a moment with her. In my extensive career of interviewing hundreds of individuals, Judy stands out as the strongest person I have ever encountered. Her story transcends the horrors of the past and has transformed them into inspiration, goodness, love, and above all, truth.

Judy lost her daughter Jill to lung cancer in 2016 and she recently lost her son Jeff this October. She has one daughter left and she still manages to find joy in her life. The film closes with Judy singing one of the songs she wrote while she was living with a group of other displaced children in the Swiss occupied home on Delibab. The song is simply about a rooster cooing. Judy laughs. Judy always manages to laugh.