A Purim Call for Mutual Recognition

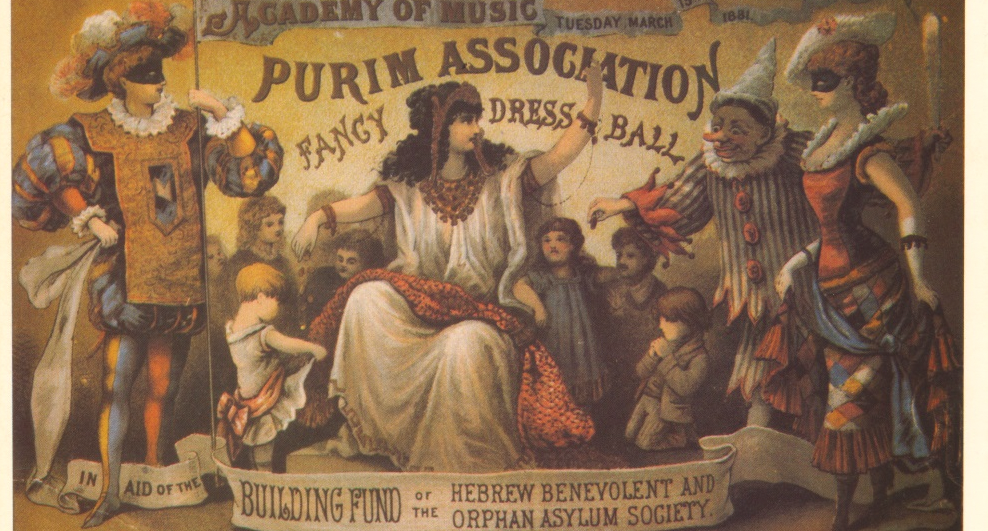

Invitation to Fancy Dress Ball, 1881; National Museum of American Jewish History

We live in an ungenerous time. Innocent mistakes are treated as punishable offenses. Well-meaning comments are turned into their opposite. Identification with others can be misconstrued as a self-serving gesture. But history tells us there are less stingy ways of thinking and feeling and so, on the eve of Purim, my mind goes back to an interesting episode from a century ago.

In October 1919, a play called Queen Esther debuted in Los Angeles’ Walker’s Auditorium. It was written by a Black woman named Clara Hulbert and staged by a Black theater company before an audience of 325 viewers, mostly Black. The California Eagle, the city’s leading African American newspaper, praised the performance:

“It was, indeed, a rich spectacle to see these colored actors and actresses represent the old Jewish heroes and heroines in Persian subjugation so richly and so realistically.

“The play, being intensely Jewish and setting forth the great and striking virtues of the ancient tribes of the Jew, cannot fail to strike into every Jewish heart and as a reminder of the glory of by-gone days this play, given by an able Negro player cast, is worth more than any other channel to help Jewish greatness and Jewish force of survival powers. It really ought to interest all lovers of humanity and all strugglers for justice, and more Negroes and Jews should see this play than Walker’s Auditorium can possibly hold.”

From today’s perspective, it may seem strange that Black actors would play Jews in a tribute to “Jewish greatness” and “Jewish survival.” But it makes sense when one considers that 1919 was a terrible year for Blacks and Jews. Pogroms raged across eastern Europe; white mobs brutalized Blacks in cities around the United States; antisemitism was becoming entrenched in American society; and the KKK was poised to undergo a national revival. In that context, Hulbert looked at the Jews and saw something familiar.

A month before the opening of Queen Esther, a 51-year-old, German-Jewish immigrant named Louis Michel published an affirmation of Black pride. His article, appearing in The California Eagle, was called “The Black Man: If I Were a Colored Man What Would I Do?” Michel declared:

“If I were born of Negro parentage…I would deem myself glorified and hallowed not to belong to the minions of tyranny, the upholders of race prejudice and unjust racial persecution. I would thank God that I was greatly fortified in my position to be in the right, whilst my foes were in the weak position of the wrong and in the final analysis of justice and fair play would be on the losing, but my comrades with myself, on the justly vindicated and finally winning side of the future!”

The very premise of Michel’s article might strike some people as offensive today. Who was he to presume that he could place himself in the mind of a Black person? But it did not bother The California Eagle’s editor. He endorsed Michel as a “full-blooded Jew” and published other pieces – essays, poetry – by him. Readers from across the country sent letters of praise.

Who was Louis Michel? The historical record is scant but, besides his age and country of origin, it shows that Michel was an avowed socialist, a Zionist, and a pan-Africanist. He proclaimed this in a telegram to the first convention of Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association in Madison Square Garden. Michel’s message read, “I join heartily and unflinchingly in your historical movement for the reclamation of Africa. There is no justice and no peace in this world until the Jew and the Negro both control side by side Palestine and Africa.” The delegates broke into applause.

Not all Jews shared Michel’s opposition to racism, and he acknowledged that. He regarded some of his fellow “racemen” as “contemptible hypocrites” because they did nothing “to help the tortured Negro of America to regain his compromised rights.” But he assured readers of The California Eagle that the majority of Jews “feel for the suffering Negro,” even if they “fear to speak up.” Michel let it be known that “This writer has no fear and he deems it his duty to speak up regardless of results.”

Michel stood by his principles. When he discovered that his employer, the Starr Piano Company, imposed unfavorable terms on Black customers, Michel objected. In a letter to his manager, he wrote that he and his wife “would rather die with the sustaining honor left behind our dead bodies that we, as Jews, were not fiendish persecutors, but real true friends of the Negroes, our Black brothers and sisters, than to be known as narrow-minded bigots that loved the Whites for their money and hated the Negroes for their color.” Michel quit his job shortly thereafter.

It is not known whether Michel and Hulbert ever met. But their writings suggest they would have perceived one another with mutual recognition. A century later, may we permit a similar level of imagination today?

Oppression and liberation are the great themes of Jewish history and Black history. Hulbert and Michel knew this. Purim reminds us of this. And it is our obligation to honor this shared heritage in our own lives.

Tony Michels teaches American Jewish History at University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he serves as Director of the Mosse/Weinstein Center for Jewish Studies. He is author of A Fire In Their Hearts: Yiddish Socialists in New York (which with won the Salo Baron Prize from the American Academy of Jewish Research for the Best First Book in Jewish Studies), editor of Jewish Radicals: A Documentary History; and co-editor of The Cambridge History of Judaism. Volume Eight: The Modern World, 1815-2000. His articles and reviews have appeared in the Forward, Slate, Jacobin, Nextbook, Guilt & Pleasure Quarterly, Heckler, and other publications. Michels is currently writing a book on American Jews and the Russian Revolution.